Agroecology is, at its core, both a practical approach and a social movement. It merges ecological principles with social justice, standing for grassroots self-empowerment from the bottom up. The human right to food is enshrined in international law and obliges signatory states to implement it in their national policies. The two concepts are most powerful in the fight against global hunger and food insecurity when they are put in relation to one another.

Civil society has played a key role in bringing agroecology into mainstream political discourse – even up to the level of national governance. But what exactly is agroecology? How does it differ from organic farming? Why has it become such an important concept for social movements around the world? And how does it relate to the right to food?

A Brief History of Agroecology

Campesinos: Kaqchikel Maya aus Guatemala schufen die Campesino a Campesino Bewegung (©Steve Richards, CC BY 2.0)

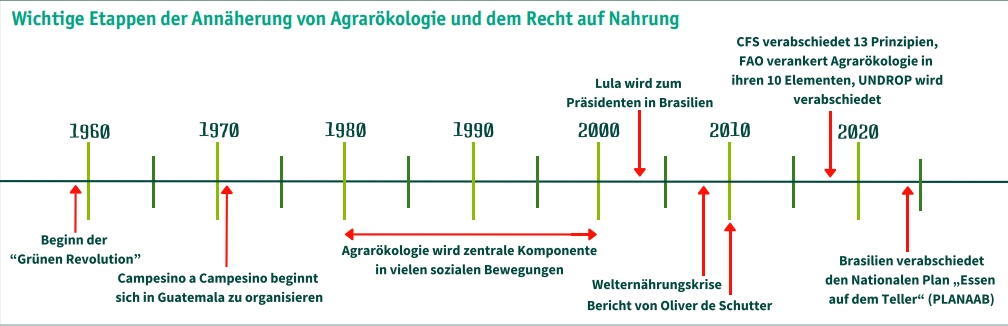

The origins of agroecology as a movement lie in the collective resistance to the industrialization of agriculture. From the late 1950s onwards, the concept of the Green Revolution was spread globally at great expense by the Global North. Backed by powerful donors like the Rockefeller- and Ford foundation, particularly the U.S. government aggressively promoted the use of industrial seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and chemical pesticides globally. Farmers worldwide were forced into debt to afford these inputs. Depleted soil, dependence on chemicals and an endless spiral of debt continue to drive farmers to take their lives – every single day.

Agroecology is the global success story of those who stood up to this system. One of its earliest examples is the Campesino a Campesino movement in Guatemala. In the early 1970s, in response to the ever-tightening grip of agribusiness, Kaqchikel Maya organized themselves to revive their traditional farming practices. They set up “demonstration fields” and shared the new knowledge amongst each other, such as the production of organic fertilizers as well as diversification through traditional seed varieties. These practices improved yields and incomes, enabling the Kaqchikel to buy back lost land and redistribute it among themselves. Due to state repression, many were forced into exile across countries in Central America where they reorganized and spread their movement. Their organizing capabilities as well as their self-empowering pedagogies make the movement a living symbol for a different way of living together.

The Uncomfortable Diversity of Agroecology

Agroecology takes countless forms around the world: school gardens in Uganda, which reintroduce traditional food to younger generations; Eco-Swaraj communities in India where women reclaimed traditional seeds through self-help groups and strengthened their role in local decision-making processes; community supported agriculture, cooperative supermarkets and food councils in Brazil or Europe.

While agroecology certainly entails a shift from chemically intensive agriculture to ecologically sound and locally rooted food systems, it encompasses far more. It embodies a vision of social justice and participation; ecological, economic, cultural, and political innovation; and above all, how people (re-)organize themselves in a variety of ways to provide themselves and others with healthy food. In other words, agroecology is a living framework of how we can work together from bottom up to transform our food systems by rebalancing global and local power dynamics and create fairer systems of human coexistence.

Agrarökologie ist mehr als „nur“ Öko

Agroecology and the Right to Food: Converging Paths

From the 1980s through the 1990s, social movements increasingly embraced agroecology as a core paradigm. Most states remained either inactive or obstructive. A shift began in earnest during the 2008 global food crisis, when the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD) issued a landmark report. Grounded in agroecological science, it made one thing abundantly clear: business-as-usual in food systems was no longer a viable option.

Building on these findings, Olivier de Schuter, former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, set a milestone for the integration of agroecology and the right to food with his 2010 report to the UN Human Rights Council. De Schuter proved that agroecological approaches have greatly improved the supply of healthy food in many regions of the world compared to conventional agriculture.

Because the right to food obligates states to take all necessary steps to ensure adequate nutrition for their populations, De Schutter drew a clear human rights-based conclusion: governments are duty-bound to create enabling conditions for agroecology.

Institutional Recognition and Global Momentum

The report strengthened agroecology at the UN level, culminating in the publication of the 13 Common Principles of Agroecology by the UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS) in 2018. In the same year, agroecology was embedded in the United Nations through the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) 10 elements. These frameworks underscore the alignment between agroecology and the right to food, particularly in terms of key shared principles: equitable access to land, water, and seed, and inclusive participation in decision-making. Agroecology has been integrated into all CFS resolutions since 2018.

Also in 2018, another milestone was reached with the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP). The declaration, rooted in the right to food, was the result of 17 years of advocacy by social movements. It is the first international legal instrument to codify the obligation—first outlined by De Schutter—for states to support agroecology as part of their human rights duties. UNDROP thus serves both as a legal foundation as well as a strategic tool for an agroecological, rights-based transformation of our food systems.

Brazil Leads the Way

In 2003, during President Lula da Silva’s first term, a new era of food policy began. One of the most significant developments was the revitalization of the National Council on Food and Nutrition Security (CONSEA), which institutionalized the principle of participatory governance. Composed of two-thirds civil society delegates and one-third government representatives, CONSEA operates at local, regional, and national levels and remains Brazil’s most influential advisory body on food policy.

A flagship initiative merging agroecology and the right to food is Brazil’s public food procurement program. Driven by CONSEA, the state purchases food from small-scale agroecological farmers and distributes it to social and state institutions such as schools, hospitals, and care homes. School feeding legislation mandates that at least 30% of government food procurement budgets go to family farms. All students receive a free lunch. Through this lever of public food procurement, Brazil has managed to drastically reduce hunger and simultaneously increase the income of countless small-scale farmers who benefit from guaranteed purchases.

On World Food Day in October 2024, Brazil launched a new national initiative: “Food on Every Plate” (PLANAAB). The plan rests on the pillars of the right to food, food sovereignty, and agroecological transformation. Measures include creating new local markets, expanding agroforestry systems, strengthening traditional seed systems, and increasing the area of land used for the cultivation of staple foods by smallholder farmers.

The diverse global examples of agroecology make clear that it is a movement in which we all can participate. And based on international human rights law, we can – and must – hold governments accountable for strengthening our backs. Brazil has shown how this can be achieved in practice. It’s time for other countries to follow suit! The agricultural policy dialogue between Brazil and Germany is a first step in this direction.

By Jan Dreier and Stig Tanzmann

Author information:

Jan Dreier is Officer for the Right to Food at FIAN Germany. Stig Tanzmann is Officer for Agriculture at Bread for the World.